By Tom Adkinson

Nov 28, 2025

|

|---|

| One more sandhill crane in this group flying over Wheeler National Wildlife Refuge would have made an even dozen. Approximately 20,000 visit every winter. Photo by George Lee |

DECATUR, Ala. – When cold weather rolls in, everyone starts thinking about big birds – turkeys. However, folks in North Alabama start thinking about another big species, one that comes to spend part of the winter near Decatur, and which then attracts travelers who want to see them. Those other big birds – sandhill cranes – are great for the tourism industry.

|

|---|

| Sandhill cranes by the hundreds – and sometimes thousands – are easy to see from the refuge’s heated, two-story observation building. Image by Tom Adkinson |

Wheeler National Wildlife Refuge is the destination for more than 20,000 sandhill cranes, plus a handful of rare and endangered whooping cranes. Plenty of other birds are at the refuge, too. It also shelters the largest population of wintering ducks in Alabama – 50,000 mallards, gadwalls, northern shovelers, ringnecks, green-winged teals, blue-winged teals, widgeons, and other species.

|

|---|

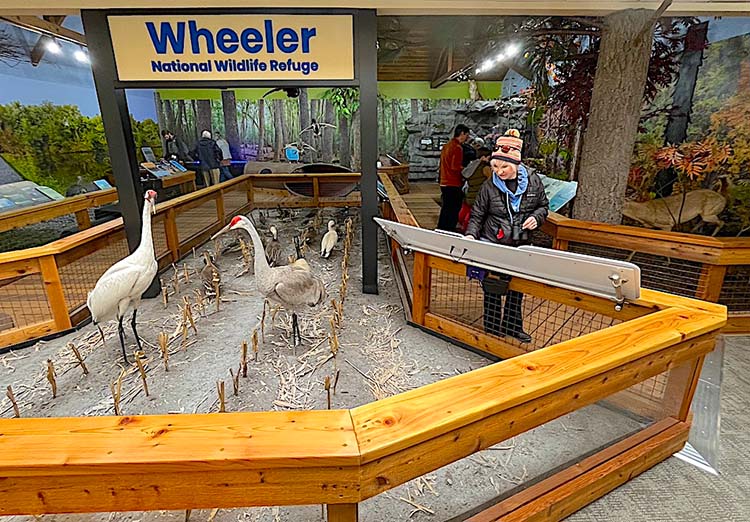

| Taxidermy displays at the refuge’s visitor center make it clear just how big the migrating cranes really are. Image by Tom Adkinson |

“Wheeler National Wildlife Refuge is appealing year-round, but it’s more exciting this time of year,” said David Young, visitor services manager for the 35,000-acre refuge along the Tennessee River near the Alabama-Tennessee state line and about 30 miles west of Huntsville.

|

|---|

| Sandhill cranes enjoy the wetlands of the refuge, where some fields are cultivated and where farmers leave corn and other grains unharvested. Image by George Lee |

The refuge makes it easy to observe the long-legged cranes. A two-story observation building is a short walk down a gravel path from a display-packed visitor center. It is heated, contains communal telescopes, and has a speaker system that carries the chatter of the cranes inside. The birds don’t know you are there because the building’s huge glass windows are made of one-way glass. Windowless viewing blinds for serious photographers are nearby.

Adult sandhill cranes can stand 4.5 feet tall and have a wingspan of more than six feet. Their plumage is mostly a muted gray or ochre, but they sport distinctive red forehead feathers that surround their eyes. They have long, pointed bills, and their necks, which curve when they are on the ground, straighten out in flight, while their skinny legs trail behind. Seeing just one – or several dozen – take flight is majestic.

|

|---|

| Two young visitors take turns getting closeup looks at the wintering sandhill cranes through a telescope in the observation building. Image by Tom Adkinson |

Young, his co-workers, and volunteers spread out across the refuge to count the cranes every two weeks. The peak population period is mid-November to mid-February. The cranes that are luxuriating in the mild weather of the Mid-South eventually head north to the Great Lakes region and into Canada for nesting. Some sandhills, though not necessarily the ones you will see, fly all the way to Siberia.

Don’t expect to see a whooping crane, but do be observant. Whooping cranes very much resemble sandhill cranes, but they are even bigger, and their plumage is mainly white. I was in the refuge’s observation building recently, and while marveling at the thousands of sandhill cranes right in front of me, another visitor spotted a whooping crane in the crowd. It was a needle-in-a-haystack moment, but a telescope and the red bands that conservationists had put on the whooping crane’s legs made it happen.

Seeing a whooping crane is a thrill because there are so few. In 1941, only 15 whooping cranes existed in the world. Conservation efforts and propagation schemes very gradually boosted that number, but the total population today is still only 800. Ten to 20 show up at Wheeler NWR every winter, according to Young.

|

|---|

| The wingspan of sandhill cranes can be more than six feet. This crane will migrate north to the Great Lakes region or beyond for nesting. Image by George Lee |

The Tennessee River, wetlands, and open fields attract the cranes and waterfowl. Of the refuge’s 35,000 acres, about 4,000 are leased to farmers who grow corn, rice, millet, and soybeans. At harvest time, 15 to 20 percent of the crops are left for the feathered visitors.

The refuge is one of 50 stops on the North Alabama Birding Trail, which is popular with birders all year. Young reports that more than 300 species have been identified here.

“April is the superhighway for songbirds,” Young said. Some of those transient visitors have wintered in Central America and South America.

(Event note: The 2026 Festival of the Cranes is Jan. 9-11. It features hikes, nature programs, and talks organized by Friends of Wheeler NWR.)

Trip-planning resources: Wheeler Wildlife Refuge, FriendsOfWheelerNWR.org, and NorthAlabama.org

Travel writer Tom Adkinson’s book, 100 Things To Do in Nashville Before You Die, is available at Amazon.com.)