Remembering on the 46th anniversary of the Beck House

We would have preferred that the house not be sold

to a member of the Negro race.

Group of Ku Klux Klan members with cross burning behind them in Knoxville, Tennessee. This photo was taken during a Ku Klux Klan initiation ceremony in Knoxville, in a field off Wilson road. Photo from the Library of Congress. |

Helen Mae Lennon hears the hurried whispers of secrecy and the sound of hammers on wood long before she sees the bright flames lick up the sides of a 12-foot-tall cross in her front lawn. In the dark of night, men pour into the yard of her new home to construct what was meant to be a symbol of love and sacrifice to twist it for their own feelings of hatred. Helen reaches for the phone to call the police for the first time that night for help, but the police are not interested in responding. Her husband, Dr. Edgar F. Lennon, paces back and forth in the home he purchased for them, not realizing then the full implication of a Black physician moving into a rich, white neighborhood. To him, 1691 Dandridge Avenue had been simply a house for sale, a new place that he could call home. To the Ku Klux Klan, his presence was a threat to white society.

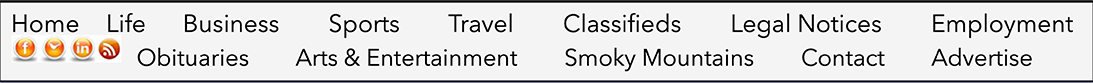

Flames burn brilliantly in the dark night of their Morningside home. White neighbors stand out on their lawns, drawn out from the sight of the haunting glow through their windows. White men stand in the Lennon yard, looking smug and proud up at their burning cross, knowing that the real display was yet to come. A sound unlike any other shakes the windows of every home in the East Knoxville neighborhood as sticks of dynamite explode underneath the cross, hurling the blazing symbol of hate across the lawn, shaking the earth beneath the white bystanders. Leaves of a large tree on the lawn ignite, burning until a company from the East Clinch Avenue fire station finally arrive to extinguish the flames.

Headlines about the fire set by the Ku Klux Klan on Dr. Edgar F. Lennon’s property from the Knoxville Journal and the Knox News Sentinel, from their archives. |

Helen Mae Lennon calls the police a second time. She calls a third time. She receives no help. The police report reads simply: “A cross was burned at 1800 Dandridge Avenue. May 25, 1947.”

As she stares at the charred remains of the cross in her yard and the green tree withered by dynamite and fire, one thought rings through her mind: Why did this happen to us?

Portion of an 1865 panorama of Knoxville taken by T. M. Schleier from top of a hill on the South Knoxville side of the Tennessee River. This section shows East Knoxville, with First Creek clearly visible as it connects to the winding Tennessee River. Photo from the UTK Digital Collection. |

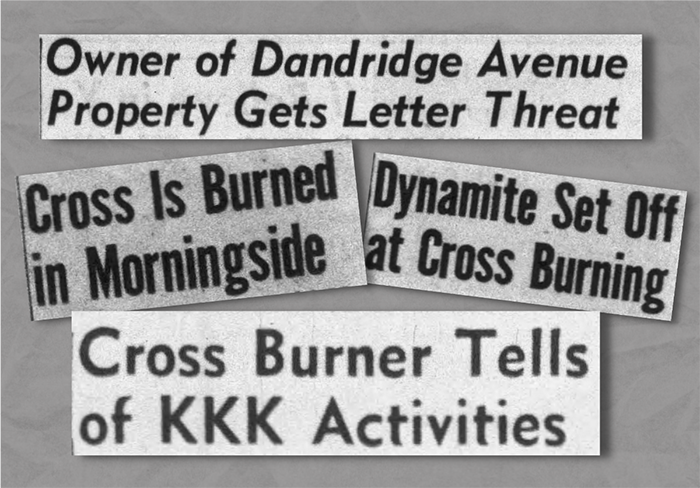

Before the Lennons moved into their Dutch Colonial style home on Dandridge Avenue, it was known as the Cowan Home by locals. The home was built in 1912 by James H. Cowan and Alice Saxton Cowan. Perhaps this is why the neighborhood reacted so violently when Dr. Lennon purchased this house from Cowan estate in 1946 for $13,500. In many ways, James and Alice represented some of the oldest white colonial settlers on this land and the neighborhood may have seen the arrival of their first Black neighbors as a threat to the status quo. James Cowan was a descendent of one of Knoxville’s leading families, the Cowans, who were among the first settlers in the city. James H. Cowan was also the great-grandson of General James White, founder of Knoxville. This brief summary of their families’ extensive ties to Knoxville’s history speaks to how wealthy and connected this family was to purchase this property and build such a house here. In 1946, it may have been unthinkable to this white neighborhood that the new resident would be Black.

Advertisement for the James H. Cowan home for sale in 1945. Courtesy of the Knoxville Journal archives. |

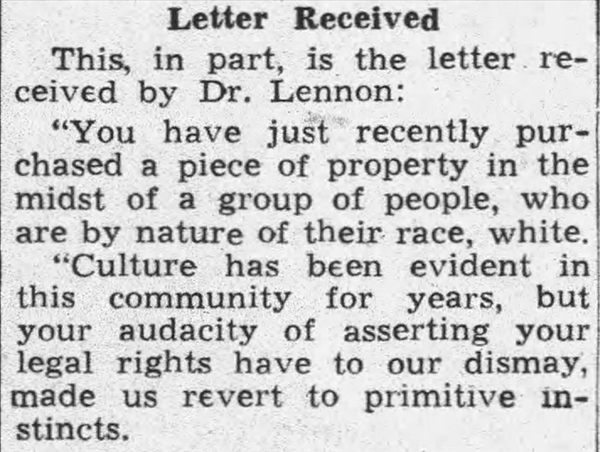

The Lennons were subjected to racial intimidation in the form of cross burnings and warnings from the Ku Klux Klan on their property before they were set to move in. In 1947, the Knox News Sentinel reported that Dr. Lennon received a threatening letter on May 16 from the KKK that demanded he move out within 24 hours. The Ku Klux Klan’s letter states that the Lennons were not wanted in the community because the Klan did not believe that integrated neighborhoods were moral or good for society. They even proposed a few “solutions” to the problem such as renting out the property to white people. With chilling hatred, the KKK letter goes on to blame the Lennons for home value decreasing, threatening them: “Last but not least, money might move you in, but money can’t change your color… However, if you insist on living in our community, please know that you will be the most unwelcome individual that lives there.”

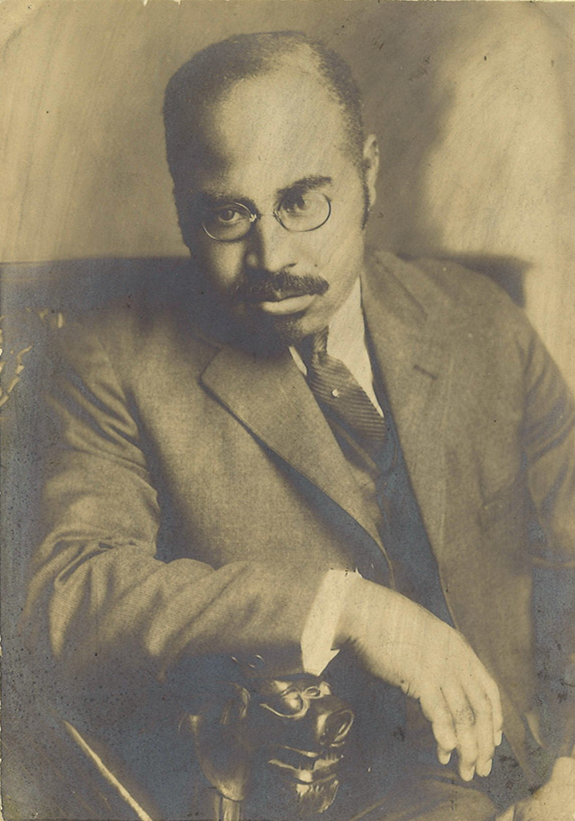

Dr. Edgar F. Lennon, prominent Black physician in Knoxville who opened the Helen Mae Lennon Hospital and nurse training school in 1923 when he was unable to practice medicine at Knoxville General Hospital due to his race. Helen, a registered nurse, operated the hospital from 1924 until its closure in 1933. Photo from the Beck collection. |

Dr. Lennon said that Dandridge Avenue was already integrated before he purchased the house. There were at least three other Black families in the 1500 block and many others lived nearby. He had no intention of making a political statement by living in a white neighborhood. He bought the home because it was for sale. In reply to the letter, Lennon simply stated: “We can’t change our color. We don’t want to change it.” The Lennons refused to be intimidated and moved into the house the following week. That’s when the KKK erected the cross on their lawn to burn as a warning that the Lennons were not welcome in their new neighborhood.

Portion of the threatening letter received by Dr. Lennon. Courtesy of the Knox News Sentinel Archives |

Dr. Lennon said that his wife Helen reported cross burnings to the police three times overnight, but the police did not seem interested in taking a report. Despite six carloads of police officers responding to the explosion, no arrests were made. Many neighbors declined to talk to the press, though they did report that they had seen a large group congregating in the lawn to set fire to the cross. While neighbors denied any involvement with the KKK and even denounced the violence, their letter to Mayor Ed Chavannes did state the following: “We would have preferred that the house not be sold to a member of the Negro race.” Residents called upon the city council to find those who committed this vandalism.

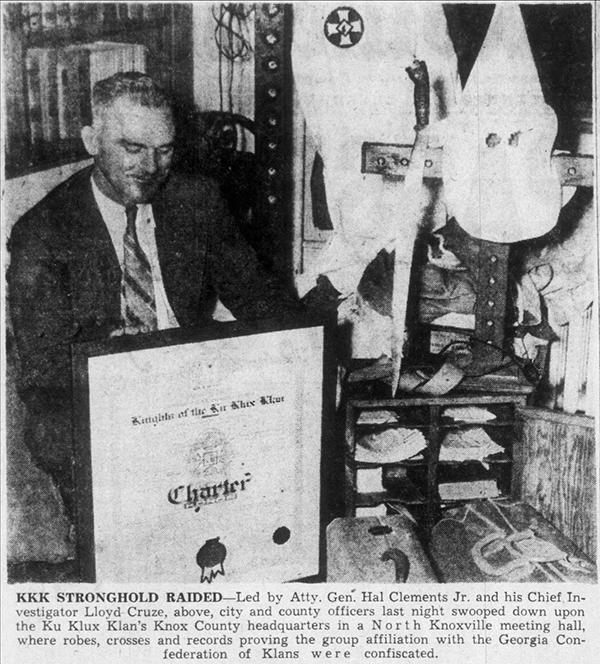

Later that month, KKK member Robert Long admitted to the cross burning and named several others as his co-conspirators. The motivation for the vandalism was “to scare the doctor out of the white neighborhood.” The Knoxville Journal reported that if he were to be charged, it would have been the first instance in which cross burners have ever had to face prosecution despite a long series of cross burnings in town. Long and three other Klansmen were released on bond and were not indicted, though the jury did sign a report saying that the KKK “fostered and condoned acts which are offenses against the criminal laws,” urging further investigation by the attorney general, the sheriff and the Police Department.

As a result of Robert Long’s confession, Knoxville police infiltrated a KKK stronghold to seize evidence in order to prepare for this case. Klan paraphernalia was confiscated by the police. No indictments were made despite the KKK having wreaked havoc on Knoxville over the years through cross burnings and other public displays of hatred. Courtesy of the Knoxville Journal Archives. |

After it became clear that the KKK would not be successful with their intimidation, the Lennons lived in the house for many years without incident. The Morningside Neighborhood continued to see more Black families moving into the area due to the Mountain View Urban Renewal project that relocated families from the Civic Coliseum area.

Beck Cultural Exchange Center in 1978. Note the presence of the beautiful red dogwood tree in the front yard. This tree was planted by the Shady Garden Club in memory of its former president, Mrs. Thomas Dixon. Shady Garden Club was one of the many community organizations that provided services to the Beck Center for its opening in 1975. Photo from the Beck Collection. |

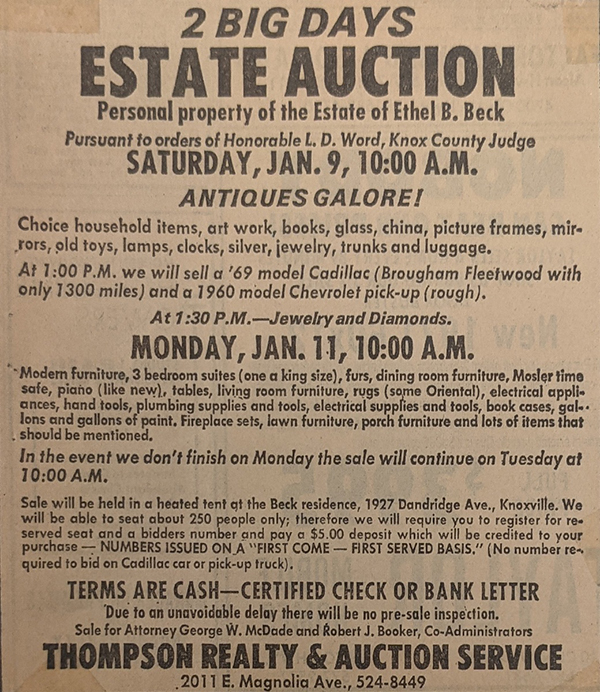

Seven years later, James and Ethel Beck purchased this home from Helen Mae Lennon, becoming the second Black family to move into this property. Unfortunately, the house was in a state of disrepair and Ethel Beck would refuse to move in until the house was renovated to her expectations, finally moving in 1969. The Becks would only be in this house for a short time before James died of health complications that same year. Mrs. Beck passed away a short time later in August 1970. In December, the Knox News Sentinel announced that Ethel Beck’s estate was to be up for auction in January of 1971. The house had an estimated value of $12,000.

Knoxville Housing Authority announced interest in renting the Beck home for a field office for the Morningside Urban Renewal Project soon after the initial announcement. The house itself was excluded from all auction advertisements afterward. The Beck estate auction attracted a crowd of over 150 people on its first day.

Advertisement for the Ethel B. Beck estate auction. Clipping of the Knoxville Journal from the Beck collection |

By August 1971, KHA had successfully set up the 1927 Dandridge Avenue home for their Morningside project site office. This office served as a place for residents of the Morningside Urban Renewal Area to receive updates on the progress of renovation work. Three site offices were established for six neighborhoods affected by the project; Neighborhoods 1 and 2, the area from Bethel Avenue south to Riverside Drive, met at the Beck home. The Morningside Project sought to be more balanced than previous projects, inviting community involvement with redevelopment of the area.

When the Morningside Urban Renewal Project was nearing a close in 1974, KHA polled neighborhood residents to see what they would like to become of the site. The response was overwhelmingly in favor of a cultural center in the neighborhood, and thus the Organization for the Establishment of a Cultural Center in the Morningside Area was formed in conjunction with Knoxville’s Community Development Corporation and the Knoxville Area Urban League. Mayor Kyle C. Testerman worked closely with the committee and supported their efforts to establish such a community center. Approximately 100 people attended the October 13, 1974 organizational meeting to provide background of the proposal and how such a center could be established. Most importantly, Margaret Gaiter stressed the idea behind the center would be “preservation, illustrative of the emphasis of the current urban renewal project on things other than just tearing down.”

As a result of this initial meeting, a sponsoring committee was formed and would first meet on November 2nd. Margaret Gaiter presided over the meeting. While organizational structure could be determined later on, the matter of financial backing was a more immediate need. The Morningside Urban Renewal Project was part of a federally mandated Urban Renewal program, meaning it had to abide by certain rules and regulations regarding the sale of property used as site offices. KCDC was required to sell the facility in compliance with these regulations, so raising the funds to purchase the house valued at $22,500 was necessary. Mayor Testerman promised to make available $2,500 but the rest of the money was to be provided by Bessie Brice.

Bessie Brice pictured in the 1971 Austin-East High School yearbook. Mrs. Brice taught typing at Austin High School and Austin-East High School for many years. Photo from the Beck collection. |

Bessie Brice had personal, close connections with the Beck home in that she once served alongside Ethel Beck on the Board of Directors for the Beck Home for Orphans. When the orphanage closed in the early 1950s, funds had been placed into an account after dissolution. Bessie Brice brought $20,000 to the table, but those funds came with an important caveat: in order to use this money, the center must be named in honor of the Becks. The request made sense, especially since the site was a former home of James and Ethel Beck. The committee agreed and the center was formally named Beck Cultural Exchange Center, Inc. in 1975.

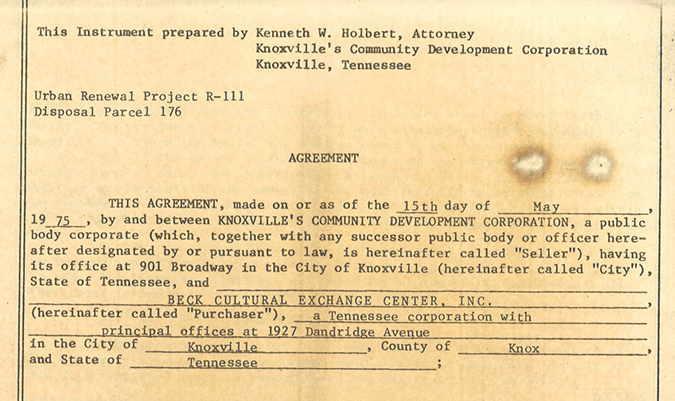

Purchase agreement for the 1927 Dandridge Avenue property dated May 15, 1975.

Document from the Beck Collection. |

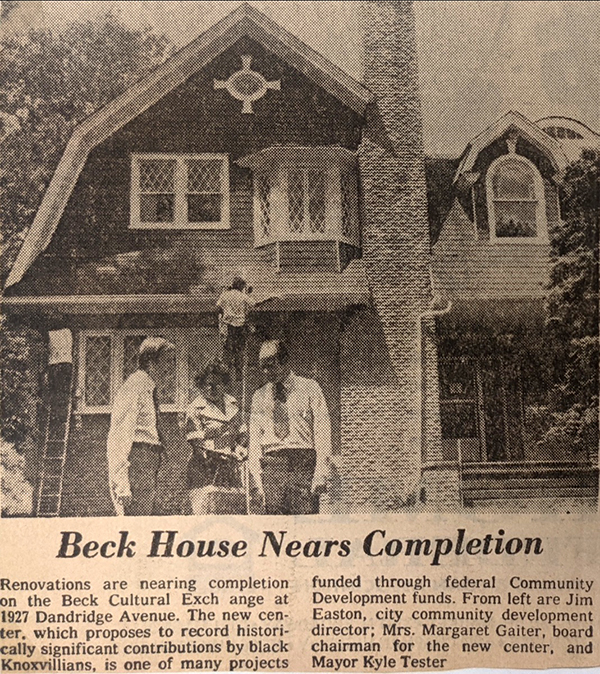

After months of committee preparation and negotiation, the Beck home was finally purchased by the Beck Cultural Exchange Center on May 15, 1975, almost thirty years after the Lennons looked out into their yard to see a burning cross. Now that the Cultural Exchange Center had a home, it could finally provide a place to preserve and promote Black history in Knoxville. Much work was needed to make the home an open and inviting space for the public and the committee set to work immediately. Community volunteers offered landscaping help, construction services, artwork, and much more. The Beck Cultural Exchange Center is truly the People’s Project as it is the culmination of determination, hard work, and most importantly, love for the community. Once the site of racial intimidation, 1927 Dandridge Avenue stands as a testament to Knoxville’s vibrant Black history and culture.

Beck House nearing completion for its opening in September, 1975. Clipping of the Knoxville Journal, August 4, 1975. Document from the Beck collection |

While the number on the house has changed over the years, it is the same house that was built in 1912. The house, today known as 1927 Dandridge Avenue, became the official home of the Beck Cultural Exchange Center, May 15, 1975.