Memorial at Luxembourg American Cemetery and Memorial; image by Jeaneane Payne

Memorial Day History

Three years after the Civil War ended, on May 5, 1868, the head of an organization of Union veterans — the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) — established Decoration Day as a time for the nation to decorate the graves of the war dead with flowers. Maj. Gen. John A. Logan declared that Decoration Day should be observed on May 30. It is believed that date was chosen because flowers would be in bloom all over the country.

The first large observance was held that year at Arlington National Cemetery, across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C.

The ceremonies centered around the mourning-draped veranda of the Arlington mansion, once the home of Gen. Robert E. Lee. Various Washington officials, including Gen. and Mrs. Ulysses S. Grant, presided over the ceremonies. After speeches, children from the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Orphan Home and members of the GAR made their way through the cemetery, strewing flowers on both Union and Confederate graves, reciting prayers and singing hymns.

Local Observances Claim To Be First Local springtime tributes to the Civil War dead already had been held in various places. One of the first occurred in Columbus, Miss., April 25, 1866, when a group of women visited a cemetery to decorate the graves of Confederate soldiers who had fallen in battle at Shiloh. Nearby were the graves of Union soldiers, neglected because they were the enemy. Disturbed at the sight of the bare graves, the women placed some of their flowers on those graves, as well.

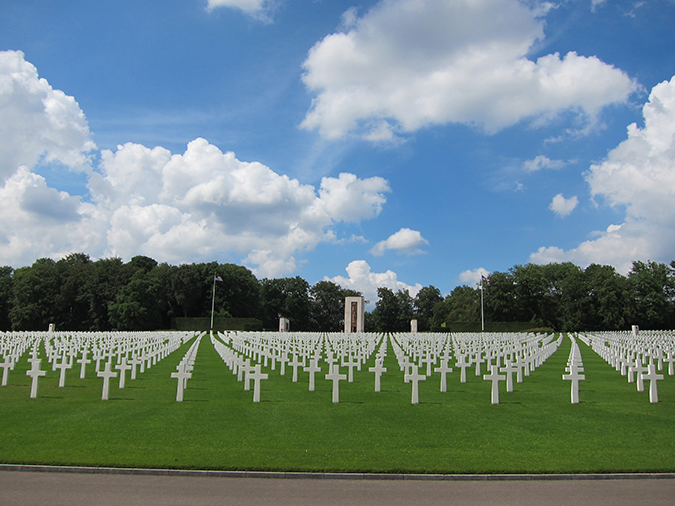

Luxembourg American Cemetery and Memorial; image by Jeaneane Payne

Today, cities in the North and the South claim to be the birthplace of Memorial Day in 1866. Both Macon and Columbus, Ga., claim the title, as well as Richmond, Va. The village of Boalsburg, Pa., claims it began there two years earlier. A stone in a Carbondale, Ill., cemetery carries the statement that the first Decoration Day ceremony took place there on April 29, 1866. Carbondale was the wartime home of Gen. Logan. Approximately 25 places have been named in connection with the origin of Memorial Day, many of them in the South where most of the war dead were buried.

Official Birthplace Declared In 1966, Congress and President Lyndon Johnson declared Waterloo, N.Y., the “birthplace” of Memorial Day. There, a ceremony on May 5, 1866, honored local veterans who had fought in the Civil War. Businesses closed and residents flew flags at half-staff. Supporters of Waterloo’s claim say earlier observances in other places were either informal, not community-wide or one-time events.

By the end of the 19th century, Memorial Day ceremonies were being held on May 30 throughout the nation. State legislatures passed proclamations designating the day, and the Army and Navy adopted regulations for proper observance at their facilities.

It was not until after World War I, however, that the day was expanded to honor those who have died in all American wars. In 1971, Memorial Day was declared a national holiday by an act of Congress, though it is still often called Decoration Day. It was then also placed on the last Monday in May, as were some other federal holidays.

Luxembourg American Cemetery and Memorial; image by Jeaneane Payne

Some States Have Confederate Observances Many Southern states also have their own days for honoring the Confederate dead. Mississippi celebrates Confederate Memorial Day on the last Monday of April, Alabama on the fourth Monday of April, and Georgia on April 26. North and South Carolina observe it on May 10, Louisiana on June 3 and Tennessee calls that date Confederate Decoration Day. Texas celebrates Confederate Heroes Day January 19 and Virginia calls the last Monday in May Confederate Memorial Day.

Gen. Logan’s order for his posts to decorate graves in 1868 “with the choicest flowers of springtime” urged: “We should guard their graves with sacred vigilance. ... Let pleasant paths invite the coming and going of reverent visitors and fond mourners. Let no neglect, no ravages of time, testify to the present or to the coming generations that we have forgotten as a people the cost of a free and undivided republic.”

The crowd attending the first Memorial Day ceremony at Arlington National Cemetery was approximately the same size as those that attend today’s observance, about 5,000 people. Then, as now, small American flags were placed on each grave — a tradition followed at many national cemeteries today. In recent years, the custom has grown in many families to decorate the graves of all departed loved ones.

The origins of special services to honor those who die in war can be found in antiquity. The Athenian leader Pericles offered a tribute to the fallen heroes of the Peloponnesian War over 24 centuries ago that could be applied today to the 1.1 million Americans who have died in the nation’s wars: “Not only are they commemorated by columns and inscriptions, but there dwells also an unwritten memorial of them, graven not on stone but in the hearts of men.”

U.S. soldier food rations during WWII; image by Jeaneane Payne at the

General Patton War Museum in Luxembourg.

To ensure the sacrifices of America ’s fallen heroes are never forgotten, in December 2000, the U.S. Congress passed and the president signed into law “The National Moment of Remembrance Act,” P.L. 106-579, creating the White House Commission on the National Moment of Remembrance. The commission’s charter is to “encourage the people of the United States to give something back to their country, which provides them so much freedom and opportunity” by encouraging and coordinating commemorations in the United States of Memorial Day and the National Moment of Remembrance.

The National Moment of Remembrance encourages all Americans to pause wherever they are at 3 p.m. local time on Memorial Day for a minute of silence to remember and honor those who have died in service to the nation. As Moment of Remembrance founder Carmella LaSpada states: “It’s a way we can all help put the memorial back in Memorial Day.”

Arlington National Cemetery, Arlington, Virginia

Tomb of the Unknown, Arlington National Cemetery; courtesy of U.S. Army

Arlington National Cemetery, the most famous cemetery in the country, is the final resting place for many of our nation’s greatest heroes, including more than 300,000 veterans of every American conflict, from the Revolutionary War to Iraq and Afghanistan. Since its founding in 1866, Arlington National Cemetery has provided a solemn place to reflect upon the sacrifices made by the men and women of the United States Armed Forces in the name of our country.

The cemetery property is on the former grounds of Arlington House, the mansion of George Washington Parke Custis, the adopted grandson of President George Washington, and his wife, Mary Lee Fitzhugh. Custis selected English architect George Hadfield to design his mansion atop a hill overlooking Washington. Custis built the house in stages, first the north wing in 1802, the south wing in 1804, and finally the central section connecting the two in 1818. In 1831, the couple’s only child, Mary Anna Randolph Custis, married a childhood friend and distant cousin, Robert E. Lee, at Arlington House. Mary and George Custis lived at Arlington until their deaths in 1853 and 1857, respectively, passing the property on to Mary Anna. Although Robert E. Lee never owned the property, he and Mary Anna lived there until 1861 when Virginia seceded from the Union and Lee took command of the Virginia State Military while Mary Anna took safety elsewhere. Lee never returned to Arlington House.

In 1864, the Federal Government repossessed the property over a failure to pay taxes and put it up for auction where a tax commissioner purchased the property for government, military, charitable, and educational purposes. Lee’s son, Custis Lee, sued over the confiscation of the property, and in 1882, the Supreme Court ordered the land returned to the Lee family. The following year Congress purchased the property outright.

On June 15, 1864, the Arlington House property and 200 acres of surrounding land were designated as a military cemetery as Quartermaster General Montgomery C. Meigs wanted to ensure that Lee could not return to the site. The first burial at Arlington National Cemetery was that of Private William Henry Christman of Pennsylvania, who lies in Section 27, Lot 19.

On average, 28 burials occur each weekday, for a total of nearly 6,900 each year. Flags at Arlington National Cemetery are flown at half-staff from 30 minutes prior to the first funeral until 30 minutes past the last funeral. Arlington National Cemetery burial eligibility requirements are stricter than all other national cemeteries. Please see the Arlington National Cemetery website for the complete eligibility requirements. Today the cemetery covers over 600 acres and contains the remains of more than 300,000 veterans in 70 burial sections, and 38,500 remains in the eight columbariums. The curvilinear pathways of the cemetery conform to the natural topography of the site, and much of the site is naturally landscaped, although several major pathways, particularly at the southeast corner of the grounds, are lined with trees. Throughout the cemetery, monuments are placed atop prominent hills, many providing visual and symbolic links to Washington, DC, located across the Potomac River.

Section 27 contains the remains of more than 3,800 former slaves who resided in the Freedman’s Village on the cemetery grounds. Freed slaves were allowed to farm on this land from 1863 to 1883, and those who died while residing in the village were buried here.

Confederates were originally buried in several different sections of the cemetery using headstones that were the same as those used to mark the graves of civilians. Beginning in 1898, former Confederates led an effort to identify and mark Confederate burials. Legislation in 1900 appropriated funds to reinter over 250 Confederates, who were already buried in Arlington Cemetery and others from the National Soldiers Home National Cemetery, to a section of Arlington National Cemetery. The legislation required that a "proper headstone" be used for the reinterments. The headstone that was selected is approximately the same size as the Union headstones but with a pointed top to differentiate the Confederate burials. This pointed headstone became the standard headstone for Confederates throughout the National Cemetery System.

The largest structure within the cemetery is the Memorial Amphitheater, located on Memorial Drive, near the center of the grounds. Dedicated on May 15, 1920, the amphitheater is used for three major ceremonies each year, the services on Easter, Memorial Day, and Veterans Day. The amphitheater is enclosed by a white marble oval colonnade, topped with a frieze inscribed with the names of 44 battles from the Revolutionary War through the Spanish-American War. The names of 14 U.S. Army Generals and 14 U.S. Navy Admirals are inscribed on panels flanking the stage. Inscribed above the west entrance is a quote from the Roman poet, Horace, which reads “Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori,” meaning, “It is sweet and fitting to die for one’s country.”

Adjacent to the amphitheater is the Tomb of the Unknowns, a burial vault containing the remains of three unidentified service members, one each from World War I, World War II, and the Korean War. A white marble sarcophagus sits atop the vaults facing Washington, and is inscribed with three Greek allegorical figures representing Peace, Victory, and Valor. The Unknown Soldier of World War I was interred in the tomb on Armistice Day in 1921 after lying in state beneath the Capitol dome after the arrival of his remains from France. The Unknown Soldiers of World War II and the Korean War were buried on May 30, 1958, after lying in state and each receiving the Medal of Honor. The Unknown Soldier of the Vietnam War, interred and presented with the Medal of Honor in 1984, was subsequently identified as Air Force 1st Lieutenant Michael J. Blassie. In 1998, Lieutenant Blassie’s remains were disinterred from the Tomb of the Unknowns and reinterred near his family’s home in St. Louis. Since then the Vietnam vault has remained vacant. The tomb is guarded continuously by the 3rd U.S. Infantry, the oldest active duty infantry unit in the Army, also known as "The Old Guard." The Old Guard is the Army's official ceremonial unit and escort to the president, and it provides security for Washington in times of national emergency or civil disturbance.

Located in Section 2 is the Civil War Unknown Monument, the first memorial at Arlington National Cemetery dedicated to unknown soldiers. Dedicated in 1866, the sarcophagus sits atop a burial vault containing the remains of 2,111 unknown soldiers recovered from Bull Run and the road to Rappahannock. The assumption is that the vault contains the remains of both Union and Confederate soldiers. For a complete list of monuments and memorials at Arlington National Cemetery, please see the cemetery’s website.

Arlington National Cemetery is the final resting place for more than 360 recipients of the Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest military decoration, given for “conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty.”

Former presidents William Howard Taft and John F. Kennedy are buried in Section 30 and near Section 5, respectively. Also buried at Arlington National Cemetery are five five-star officers: Admiral William D. Leahy, General George C. Marshall, General Henry F. Arnold, Admiral William F. Halsey, and General Omar N. Bradley. Other notable burials include Pierre Charles L’Enfant, Revolutionary War veteran and planner of the new capital city of Washington; Robert Edwin Peary, famed North Pole explorer; 12 Supreme Court justices, including 4 Chief Justices; and 19 astronauts.

Support the families of America’s fallen heroes here.

Sources: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and National Park Service